ADM and Pillsbury have tried to whack the Great Northern before.

Here is how the Buffalo Preservation Report observed the battles at the time

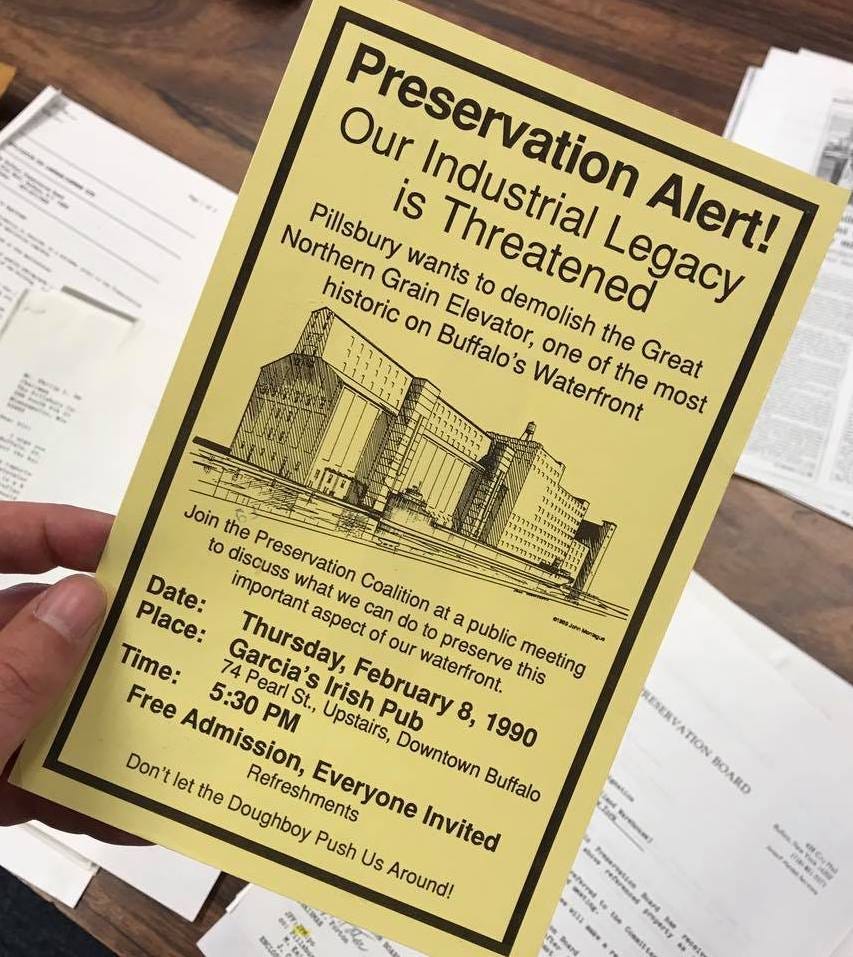

Out-of-town corporate giants have been trying to knock down the Great Northern grain elevator for decades. It began in 1989 when the Pillsbury company applied for a demolition permit. Pillsbury had been trying to reduce employment at its flour mill and the Great Northern for over a decade. In 1981 it bought the Standard Elevator on Childs Street, installed a vacuum system to unload grain ships, and stopped accepting grain at the Great Northern, which used marine legs and scoopers.

The scoopers, who constituted the last union of their kind, still had the right to unload grain at the Great Northern. Pillsbury, according to the union, wanted to end that right, and end the union, by demolishing the Great Northern. The Preservation Coalition of Erie County—the spiritual predecessor of The Campaign for Greater Buffalo—jumped into action. It wrote the 1990 landmark application that is central to the current court case to save the Great Northern, and fought off a 1995-1996 attempt by new owner ADM to demolish the elevator. Here are three of the several stories as they appeared in the Coalition’s newspaper, The Buffalo Preservation Report. The stories have been lightly edited.

ADM to city: Drop dead

City to ADM: Not so fast

Originally published in the June/July 1995 Buffalo Preservation Report

By Tim Tielman

Shortly after achieving its main objective—acquiesence from the City of Buffalo’s Preservation Board [staffed mostly by Griffin Administration holdovers at the time] to demolish the Great Northern grain elevator—owner Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) revealed its true colors by appealing to the Buffalo Common Council, asking it to drop all significant agreed-upon ‘mitigation measures’ and issue a certificate of exception for the demolition without any conditions.

After months of self-described painful, agonizing deliberations, the City Board reluctantly agreed to allow ADM to demolish the Great Northern. Three members, including Preservation Coalition President Susan McCartney, objected.

But the battle is by no means over. The matter went back to the Common Council for review. The Common Council’s Legislation Committee, meeting May 9, roundly criticized the Preservation Board’s handling of the EIS, and tabled the item until May 23.

At that meeting, Preservation Coalition President Susan McCartney told the Council ADM was “arrogant, manipulative, and downright sneaky” in its attempts to get the landmark demolished.

Coalition Trustee Ruth Heintz angrily stated “I’ve watched the city taken apart brick by brick and I’m sick of it.”

Coalition member Scott Field denounced ADM, saying “The Buffalo Preservation Board made a deal with the devil and now the devil has come to collect our soul.”

A thorough analysis of the Environmental Impact Statement was made by Charles Hendler (Buffalo Preservation Report, Feb./March 1995), who pointed out that assertions of financial losses weren’t backed up by ADM’s own figures.

Councilmember David Franczyk castigated ADM, exclaiming “They are trying to make fools of the Common Council.”

Questioned by the Council as to why ADM wanted significant mitigation measures dropped, the local plant manager said the company thought it would have difficulty dealing with the Preservation Board.

Under questioning by Committee Chair Alfred Coppola, ADM admitted full knowledge of the Great Northern’s landmark status, and that it never made any attempt to maintain the building.

ADM’s request is on hold pending a meeting of interested parties before the Legislation Committee on Wednesday, May 31.

Preservationists claim ADM’s actions call into question its motives in demolishing the Great Northern. ADM has claimed it needs to tear down the Great Northern to build a new grain elevator, a proposal it added to its demolition request in the last year.

The decision by the Buffalo Preservation Board appeared to hinge upon claims by ADM of economic losses to the city if ADM could not carry out its plans. ADM has not considered alternatives that would allow the Great Northern to remain. Buffalo Mayor Tony Masiello, in letters responding to citizens concerned with the Great Northern’s demise, plays ADM’s economic intimidation card.

In requesting an unconditional demolition permit, it appears to many that ADM’s proposed new elevator was only a foil.

The demolition OK was consented to by the Preservation Board only after ADM had agreed to a number of so-called mitigation measures. Mitiga-tion measures are part of the environmental review process, meant to alleviate some of the harmful effects of a proposed action.

Among the mitigation measures agreed to by ADM attorneys were a bond to assure that the proposed elevator be built; construction of a scale model of the elevator; and acknowledgment by the Chairman of the Board of ADM, Dwayne Andreas that he was aware of the pending demolition.

At no time during the discussions did ADM’s representatives question ADM’s ability to carry out these mitigation measures.Saving the Great Northern to save jobs

Saving the Great Northern to save jobs

Originally published in the April/May 1996 Buffalo Preservation Report

By Tim Tielman

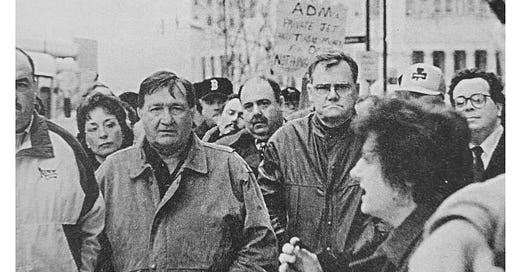

Two-hundred people gathered in the afternoon chill of March 14 to voice support for the Buffalo’s historic Great Northern grain elevator and to scorn its owner and would-be demolitionist, Archer-Daniels-Midland. ADM several years ago bought Pillsbury’s Buffalo assets.

The Preservation Coalition was joined by Local 1286 of the Longshoreman’s union, Grain Millers Local 36, Teamsters, and the Coalition for Economic Justice. Joining together to save heritage and jobs, the groups formed a coalition called Citizens Against Downsizing Buffalo To Death. ADM wants to demolish the Great Northern and abandon another elevator to build a new one with the express purpose of eliminating jobs.

The unions claim the Great Northern was closed because Pillsbury lost outside contracts on its Standard elevator, and shifted Great Northern work there because its legs were faster and the plant manager didn’t get along with the people working at the Great Northern.

Further, ADM wants to build the new elevator to eliminate the trucking jobs, elevator jobs, and scoopers jobs by accommodating self-unloading ships. About 50 people work in three shifts at the mill. It is the largest of some 30 mills producing Pillsbury products— and work would likely continue no matter what happens with the elevators, according to union officials, while demolishing the Great Northern would set off a process leading to the certain loss of 18 trucking and elevator jobs, and a reduction of 34% of scooper work.

The Great Northern opened with 3 towers (the movable steel structures which house lifting apparatus), but lost 1/3 of its lifting capacity when only two legs were replaced after a wind storm toppled all three in 1922. Adding a third leg or modernizing the other two would make the Great Northern as fast as any elevator, according to the men running the Standard.

Citizens Against Downsizing Buffalo To Death welcomes individuals and organizations to participate in its events.

The historic importance of the Great Northern

The Great Northern is unique. It is the only ‘brick box’ storage and transfer elevator in the United States. It represents an important advance in the application and aesthetics of elevator technology and a touchstone in Buffalo’s social, cultural, and economic history.

It was begun and virtually completed between February and September 1897—an astonishing pace for an elevator that was briefly the world’s largest, with a capacity of over 2,500,000 bushels.

The Great Northern and the Electric elevators (demolished in 1984), both built at the same time, were important not only for their use of electricity as a power source, but for cylindrical steel bins for grain storage. Prior to this, probably all of the grain elevators in Buffalo consisted of square wooden bins sheathed in corrugated metal or wood.

A typical wooden bin could hold 5,000 bushels of grain. The Great Northern’s primary bins could hold 74,000. In addition, wooden elevators had the disturbing habit of burning down, often within only a few years of being built.

Steel bins, apart from the odd structural defect, can last considerably longer: those in the Great Northern are original. They can, however, deform in the heat caused by fires. The Great Northern’s narrow cylindrical bins were an important engineering advance that would determine the “classic” shape of grain elevators all over the world.

The first steel elevator in the U.S. was the Washington Ave. elevator in Philadelphia, with square bins. Steel wasn’t seriously considered again until after 1895, when the Bessemer process was mature and defect-free sheet steel was cheap.

Then, the Electric and Great Northern were built in 1897, both of steel, both powered by electricity (It is believed the Electric went on-line first).

The Great Northern is the last of Buffalo’s major “working house” elevators, in which the storage bins, work spaces, and conveying apparatus are all located within a single structure. In this respect it was much like the old wooden elevators.

The Great Northern has thirty 38-foot-diameter bins, placed in three rows of 10, and eighteen 15.5-foot-diameter bins, placed in the interstices of the larger bins. The bins can withstand stresses of 17,000 pounds per square inch. A 30-inch thick brick wall encases the bins.

The brick skin serves strictly as weatherproofing and does not carry the weight of the cupola or the grain bins.

The Buffalo News covered the demonstration as well, with James Madore filing this report on the demonstration:

Local preservationists and civic leaders have joined with unions in urging Archer-Daniels-Midland Co. to scrap plans that they say will cost local jobs and destroy a historic landmark.

The diverse coalition -- calling itself Citizens Against Downsizing Buffalo to Death -- was unveiled Thursday afternoon at a downtown rally attended by about 200 people.

Standing outside the offices of Assembly minority leader Thomas M. Reynolds, they called on the Springville Republican to distance himself from GOP presidential candidate Bob Dole, who has received financial backing from ADM.

Since 1992, the Longshoremen's union has been trying to negotiate a new contract with ADM, which now operates the Pillsbury flour mill on the city's waterfront. Union Local 1286 represents about 15 grain elevator employees.

President Edward McNeight accused ADM of union-busting. He said the Illinois-based corporation wants to eliminate jobs, sick leave, severance pay and the 40-hour work week. These changes will jeopardize workplace safety, he said.

ADM executives were not immediately available for comment.

Local 1286 has banded together in a joint council with six other Longshoremen locals, plus the American Federation of Grain Millers Local 36, which represents about 65 workers at the Pillsbury/ADM flour mill on Ganson Street. Together, the unions in the joint council represent about 2,500 area workers.

But Illinois-based ADM is a giant corporation, with 1995 sales of $11.4 billion and 14,000 employees. So, union activists are reaching out to local preservationists and the Coalition for Economic Justice to put pressure on ADM by staging protests against Dole and his supporters.

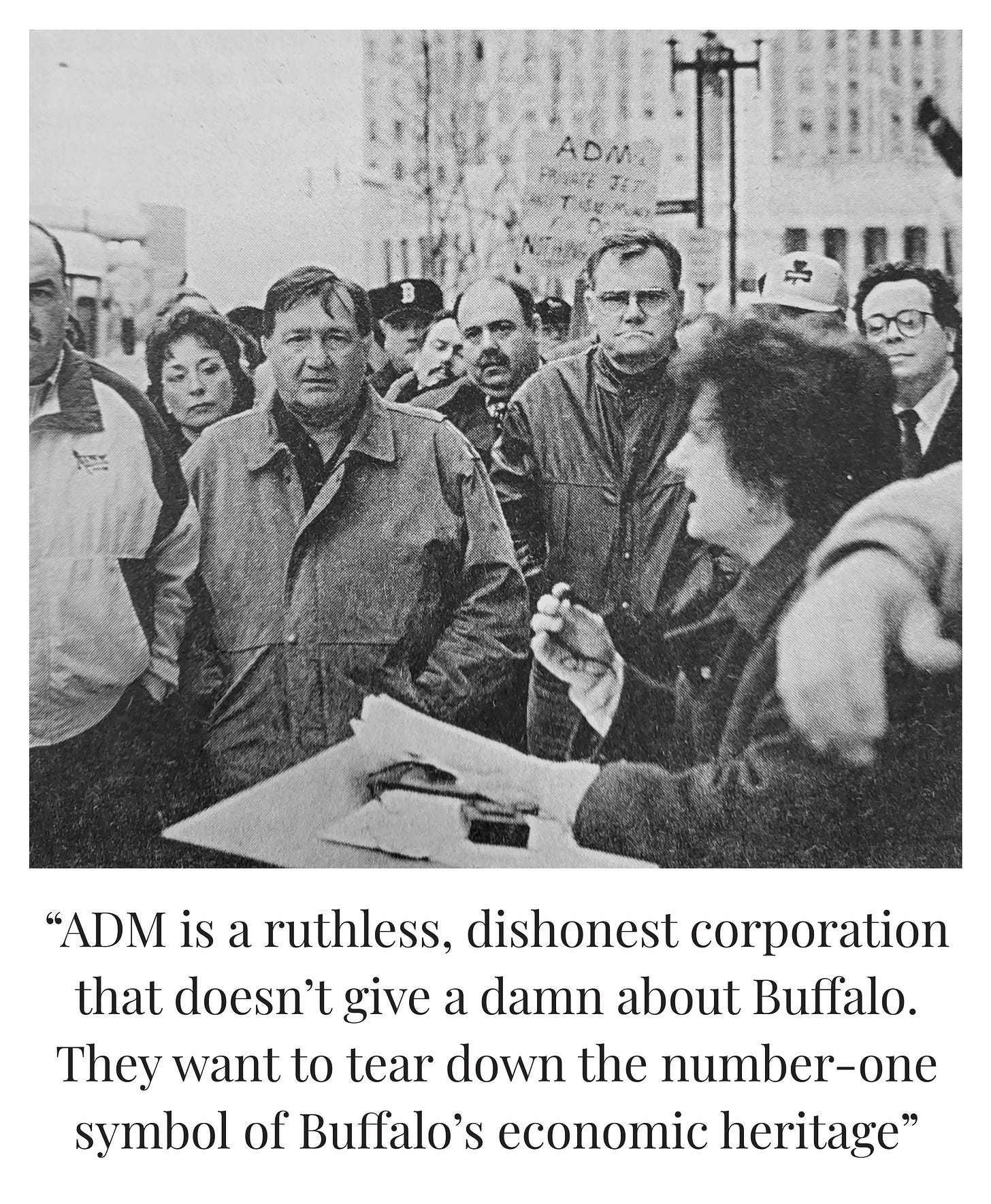

"We've joined together to fight a common enemy: ADM," said Susan McCartney, president of the Preservation Coalition of Erie County.

"ADM is a ruthless, dishonest corporation that doesn't give a damn about Buffalo. They want to tear down the No. 1 symbol of Buffalo's economic heritage," she said, referring to ADM's plan to demolish the 1897 Great Northern grain elevator and replace it with a modern facility.

ADM's plan will result in the termination of about 43 people, who operate the elevators, drive trucks and unload grain from lake freighters, Ms. McCartney said.

The speakers also blasted ADM for providing millions of dollars to the GOP and Dole, along with air travel. They accused the corporation of attempting to buy political favors.

"Bob Dole is ADM's sugar daddy," declared Richard Furlong, the union's attorney. Furlong warned Reynolds that he will be drawn into the controversy unless he withdraws his endorsement of Dole's bid for the White House.

Hope for Great Northern as new issues come to light

Originally published in the June/July 1996 Buffalo Preservation Report

By Susan McCartney

New and critical information regarding the Great Northern Elevator presented by waterfront labor unions opposing its demolition has been presented to the Common Council. The information, regarding job losses and a renovation plan that the unions claim was withheld from an environmental impact statement, was presented to the Council’s Legislation Committee, chaired by Al Coppola, on June 4. Coppola and Fillmore District Council member David Franzcyk, whose district includes the Old First Ward, traditional home of waterfront workers, co-sponsored a resolution seeking information from building owner ADM.

The unions contend that ADM’s desire to demolish the Great Northern is part and parcel of a plan to cut elevator and scooper jobs on the waterfront. Many of the workers have fond memories of working at the elevator—an imposing structure of national architectural and engineering merit—and adjacent mill. The elevator is a designated local landmark.

ADM contends it wants to demolish the landmark in order to build a modern elevator and create jobs, a contention preservationists and workers is false. If and when a new elevator is built, it would likely cost 10 elevator jobs and four dozen scooper jobs. ADM admitted to the committee that, yes, it would be eliminating permanent jobs and that the Great Northern, if demolished, would not be replaced for at least three years.

Unbiased observers could not be blamed for suddenly smelling something fishy.

The committee further learned, with records from the Department of Public Works, that onerous transportation costs related to city bridge repairs by ADM were “misleading.”

While testimony by waterfront workers and preservationists was going on, the ADM lawyer and plant manager continually rolled their eyes, smirked, cast meaningfully incredulous glances, and otherwise sought to cast the sometimes heartfelt testimony in laughable terms. Severely admonished by Council Majority Leader Rosemary LoTempio, ADM counsel, incredibly, explained that such shenanigans were necessary when trying to respond to the new evidence being presented.

The Council also learned of a study and blueprints prepared by the elevator’s previous owner, Pillsbury, to modernize and reopen the 1897 elevator, which workers allege was closed only to eliminate a union local. Unionists and preservationists have held several informational pickets of the plant manager’s Hamburg house.

You can help The Campaign save the Great Northern and in its mission to preserve and enhance all the places that make Buffalo special by making a donation on our website at GreaterBuffalo.blogs.com or scanning the qr code above.