The DL&W and the Canal District

A 19th century battle for supremacy on the waterfront and hopes for the future

A central theme of the Canal District’s history that has been shunted aside stands to reclaim its spot in the public imagination if plans to dismantle the downtown section of the Skyway come to fruition: the railroads, and specifically the storied DL&W. Buffalo was for a long time the second-largest rail center in the country, after Chicago. It is unlikely, however, that any city was as dominated by railroads as was Buffalo. Yet, little remains at the focal point of early railroad development in Buffalo, the downtown waterfront and canal district.

Well over 20,000 people worked for the railroads locally, with the New York Central; Delaware, Lackawanna & Western; Erie; and Pennsylvania being the largest. The DL&W employed over 3,000 entering the Depression. Many railroad workers were Italian men from the Canal District, according to Virginia Yans-McLaughlin, author of Family and Community, Italian Immigrants in Buffalo, 1880-1930. As is well known locally, sleeping car porters and other service staff were middle-class pioneers in Buffalo.

The Buffalo waterfront—the Canal District, to be precise—was the target of every railroad operating in the city. It was vitally important to connect with water borne goods and people. Yet this was a fairly constricted area, and there would not be room for everyone. For the roads which did have access to the docks and wharves, it figured to be a bonanza — either through direct access or by charging others for that access.

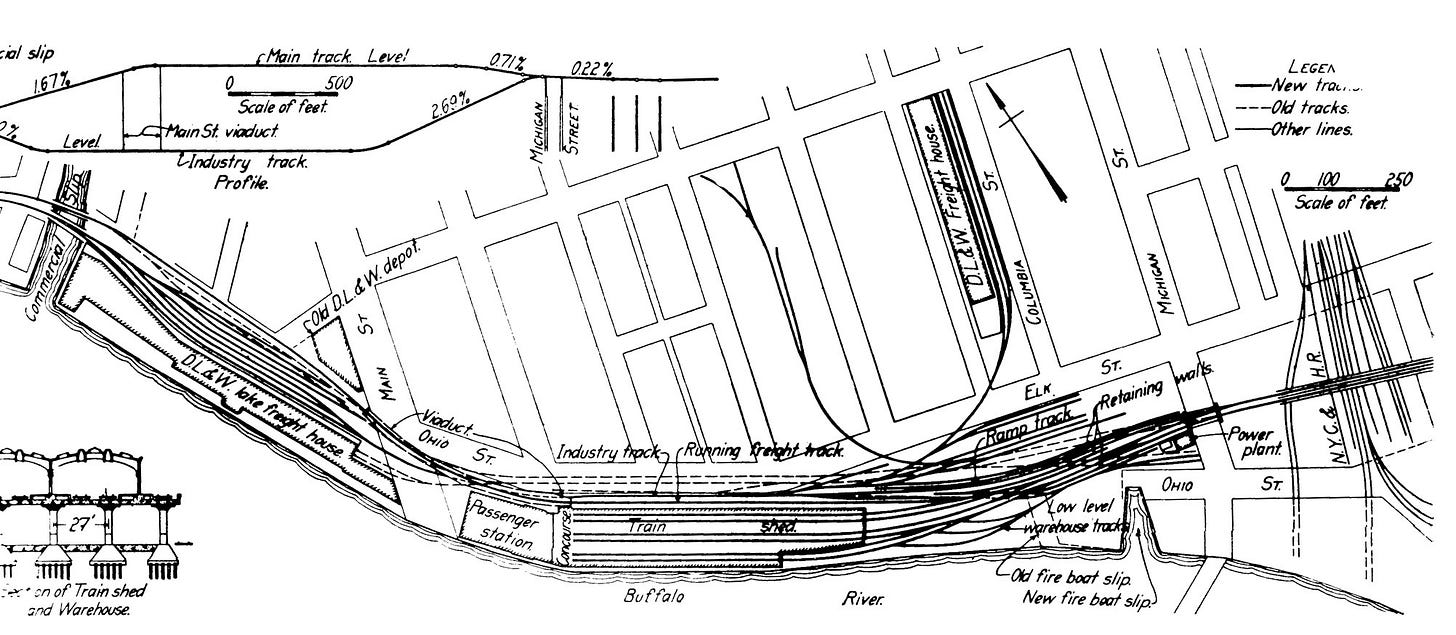

In Buffalo, the prime waterfront players came to be the Central, the DL&W, and the Lehigh (and their predecessors). The Central, as the largest 19th century railroad, got to the water first at Erie Basin. If the DL&W was to survive in the Buffalo market, it had to get to the water as well. But its path was blocked, first, by a New York Central freighthouse on Moore Street, about one-half mile east of Main Street, and secondly, by some of the most expensive commercial real estate in the country: the buildings lining Central Wharf, Prime, and Main streets.

The DL&W eventually got control of the 1840 New York Central freighthouse and built tracks right over it (at every cross street downtown the DLW had to build a trestle. The Moore Street trestle base was built right into the wall of the old NY Central building. The limestone blocks that carried the track still form part of the otherwise brick wall. In much the same way, concrete bridge abutments carrying the DL&W track over the Commercial Slip survived through the 2000’s, until destroyed under auspices of the Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation, with approval of the state historic preservation office—a decision opposed by Buffalo preservationists and academics.

The DL&W set about to buy every single waterfront building between Michigan Avenue and Lake Erie. It took decades, but it eventually was successful. By 1873 it had gotten to the Lake. It modified a former street railway depot into a passenger station in a small triangle of land formed by Main, Prime (which ran parallel to the Buffalo River, about 100 feet inland) and Dayton streets. This is across from the Sabres’ gift shop in the Key Bank Center.

The DL&W freight operations were along the Central Wharf. It demolished most of the Central Wharf buildings, with one notable exception: the Steamboat building close to Commercial Slip. There, it merely cut mammoth holes in the wall to admit freight cars. Local headquarters were in the former Aetna building on Prime Street. Along Prime Street, where it could, the railroad moved buildings it had purchased northward. The Aetna building, brick, five stories tall and over 100 feet square, was moved 50 feet north.

Then began a series of events which added up to the most amazing land grab in Buffalo history, the actual theft of Prime Street.

In retrospect, it could be said that the railroad had spent such enormous sums of money acquiring the buildings lining both sides of Prime Street that it had a proprietary interest in it. It was engaged in a Darwinian struggle with other railroads (Darwin’s Origin of the Species, originally published in 1859, was a still a hot book among a class who saw in it a justification of unrestrained self-interest: survival of the fittest was natural law).

The DL&W seemed indeed to have found a bonanza. From the moment it ran tracks out to the lake at the North Pier, today a restaurant at Erie Basin, business boomed. But the railroad was soon showing some high-handedness: it attempted to seize the dilapidated pier and rebuild it for its own purposes. Federal troops were dispatched to reclaim it. Eventually the pier was rebuilt at railroad expense as the exclusive user, while the city maintained the fiction that it was a public way (This is like Baltimore Street, the former Clark & Skinner Canal, in the Cobblestone District, which is a public street, yet closed off to the public by the Buffalo Sabres). The same scene would play itself out in the 1890s, when the pier needed to be rebuilt again.

As traffic boomed, the DL&W was getting pinched in the neck of Prime Street. The city had given it permission in the early 1870s to lay track in Prime Street, as long as the northern section of the stone street remained without track. Railroad operations obviously could monopolize any road that happened to have track across its full width.

Sam Sloan, president of the DL&W, desperate now to maintain timely operations and market share, beseeched the city to give him the full width of Prime. The city balked. Sloan, for whom the village of Sloan is named, fumed.

“I’ll have Prime Street if I have to pave it with gold,” Sloan is reported to have said after his loss in the Common Council. He was at the brink. We’ll let the Buffalo Commercial Advertiser, of May 29, 1886 take it from here: “For some time past, the Delaware Lackawanna & Western Railroad Company have been making efforts to obtain a grant from the Common Council to lay two additional tracks in Prime street, between Main and Lloyd, but for some reason, the matter hung fire, until on Monday last, in the Council, resolutions in favor of the grant were lost by a vote of 11 to 13, and the matter was referred back to the street committee… [T]he company has now, by a bold move, and night invasion, actually seized the street, and laid its tracks therein, without waiting for the city’s permission.

“Since midnight and six o’clock this morning a remarkable change took place in the aspect of Prime street…. The even, well laid passenger tracks of the Lackawanna road, on the east side of Prime, had a more complete look than two new tracks that were hastily laid early this morning by a gang of 200 men, who suddenly appeared and in the most thorough and systematic manner proceeded to lay a double track on the east side of the street, leaving of what was once a passable street, a railroad avenue with a passage to the freight cars. In the widest part of what there is now left of Prime street, two wagons can just pass each other.

“The gang of railroad employees, by a preconceived plan, evidently, arrived about 12 with ties, railroad iron and implements, and did the work so effectually that by six o’clock this morning they were able to back in on one track six cars loaded with stone, nine empty box cars and four loaded with staves and other stuff. On the second track were 14 cars loaded with railroad iron. The cars were so placed as to completely occupy the tracks… The end of the track near Lloyd street is protected by the raised wall that forms the roadway from the high grade and of course the cars are protected on that end. And at the other end the sentinel engine and two cars hold the key to the situation.

“The work of laying the track was done so rapidly, that the police even were not aware of what was going on till it was all over. Superintendent Phillips said if he had known he would have prevented the tracks being laid, no matter if the gang had been twice as large.

“The whole scheme was well planned, and all the movements kept a secret till it was carried out.

“At the City Hall the action of the railroad created general consternation and brought forth all sorts of comments on the “cheek” of the railroad. The City Attorney said that nothing could be done about the matter until the council meets on Tuesday. If he had know it in time he would have secured an injunction on the company and prevented the laying of the tracks.

“The Mayor said it was all news to him and he should have to consult the City Attorney before taking any action. The whole affair made quite a sensation in the building.”

The result? The railroad banded together a group of Canal District manufacturers to testify on its behalf, and the city took no action. Prime St. remained a public right of way, but was regularly blocked solid by rail cars. In fact, passenger trains with huge locomotives stopped in the middle of the street while passengers and baggage went to and from the station.

Later still the DL&W seized the Central Wharf itself, denying public access to this stretch of shore, guaranteed from since there ever was a city. That denial of access ended in 2008, with the reconstructed Central Wharf, the first tangible public benefit of the court-ordered master plan of 2004, the result of a lawsuit filed by Richard Berger, Fran Amendola, and Rachel Kane, on behalf of the Preservation Coalition of Erie County, led by Chair Susan McCartney and Executive Director Tim Tielman. Tielman coordinated the years-long battle in the public arena to move the state plans from a placeless shopping environment to a history-based reconstruction of the canal, street network, and buildings.

The process has been long and laborious, but could take off with the dismantling of the downtown section of the Skyway, which has blighted the area and inhibited development since the remnants of the Canal District and much of The Terrace were destroyed to accommodate speeding trucks and automobiles 65 years ago. That could also spur the redevelopment of the DL&W’s landmark train shed, in conjuction with connecting it to a the “Cloudwalk” adapted from the southern section of the former Skyway (see previous posts on Greater Buffalo for more information). The truncated Skyway, symbolic of the subsidized automobile infrastructure that was to be the death of the DL&W and just about every other railroad, and the American downtown, could be used in its new form to revive the magnificent train shed of the DL&W, and downtown Buffalo itself.

—Donna Ashby and Tim Tielman

Great and thorough article. I think this area with the aggressive DL&W also was reviewed by SCOTUS and the validity of Federal Jurisdiction was established and the docks themselves remained in Federal Ownership.

We might have to lay the LRRT tracks on the skyway overnight.