There is no emergency

New model of Great Northern makes clear the problem is cladding, not structure

By Paul McDonnell and Tim Tielman

Unless an appeals court intervenes, Buffalo is heading headlong into the avoidable destruction of one of its most significant buildings. It is doing it because of a rushed error in judgement by the person in charge of code enforcement who did not seek or gather advice from anyone except his staff and the intransigently negligent building owner. He came to the conclusion that one of the most stoutly constructed buildings in the city was in imminent danger of collapse, if its 60-foot high, 40-foot wide, 400-foot long top didn’t blow off first. He saw it as an emergency requiring the setting aside of public hearings, environmental reviews, and asbestos removal. He did not consider how the alleged danger could be abated without demolition.

Commissioner James Comerford of the Buffalo Department of Permits and Inspection Services did all of those things, and because of his unwillingness to admit to a mistake, the Great Northern grain elevator is, at the moment, at the mercy of the appeals court. Comerford’s boss, Mayor Byron Brown, insists his hands are tied and that he cannot pull back the emergency demolition order. The Campaign for Greater Buffalo, which sued to stop the demolition, has insisted since a section of brick cladding fell during a windstorm on December 11, that owner ADM’s 30-year record of negligence not be rewarded with a demolition permit, and that, since the Brown Administration issued the Order of Condemnation which called for the emergency demo, the Brown Administration could revoke it given new information.

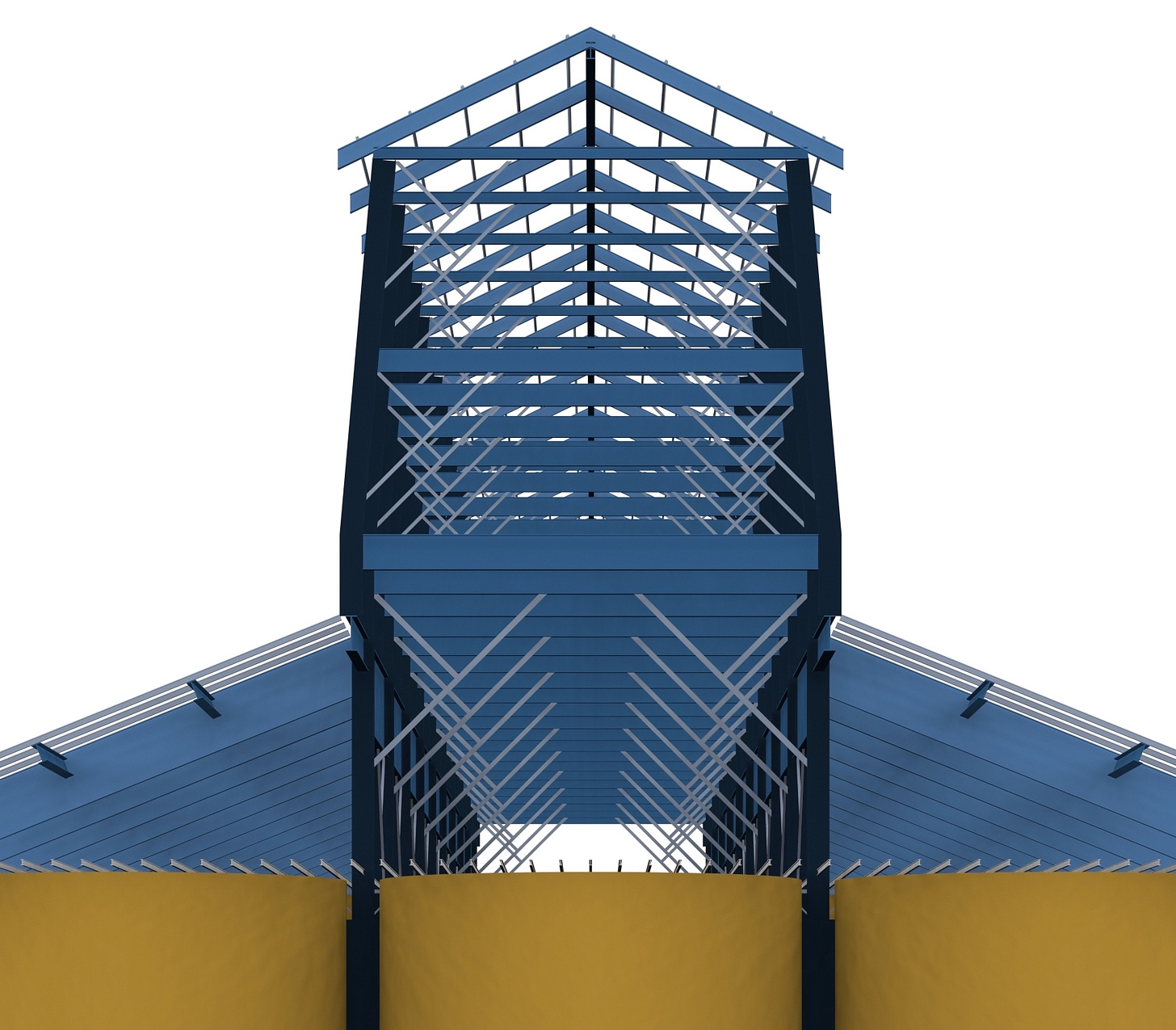

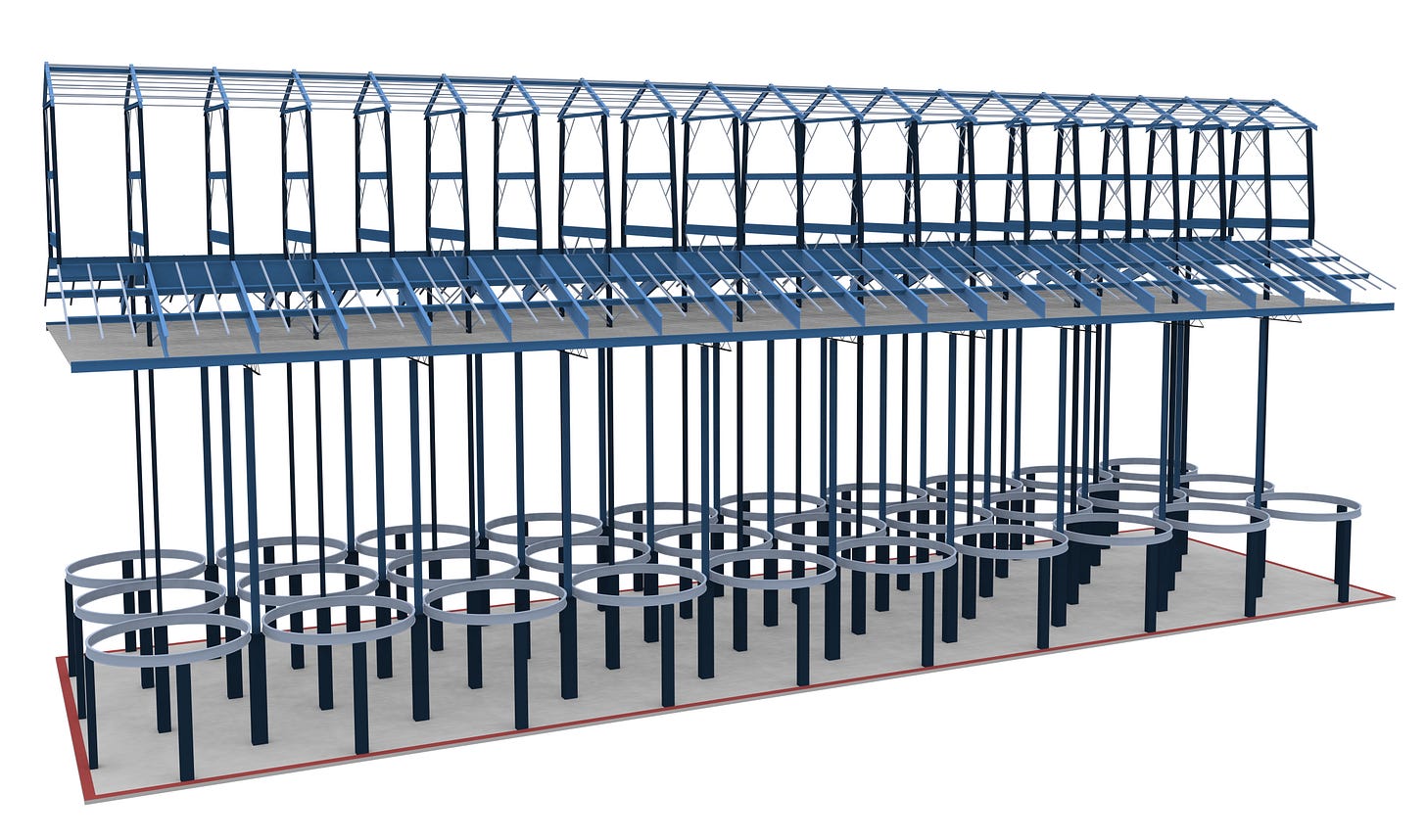

The Campaign has constructed a computer model of the Great Northern structural steel skeleton and primary steel grain bins— a new visualization based on a 125-year-old original in City Hall files.

Our immediate reaction when we heard of the failure of a brick wall at the Great Northern during a storm was that it would cause an over-reaction. We went down to inspect it on the evening of December 11, with the storm still raging. A large section of brick cladding had fallen away. As was easy to see, the structural integrity of the building was not threatened, and the brick cladding had stabilized. But the owner had been campaigning yet again to destroy it. According to Comerford, ADM had come to him “in the last year or two” for an emergency demo. It had a legal strategy to evade review, and now it an opportune moment to put it into motion.

Through training and experience, one can visualize three dimensional building from two dimensional drawings. (We both had served on the city’s preservation board for over 10 years, one of us as chair.) Thus, we understood immediately that the Great Northern wasn’t going to come down, but that it had cladding problems that could be fixed.

The Great Northern was designed as the strapping embodiment of the new age of steel and electricity, to be the largest grain elevator on earth and of a new type: It would store grain in steel cylinders set in a steel frame the size of a city block. Built the year after the world’s first skyscraper, the Guaranty building, it is taller than the Guaranty. A groundscraper 400 feet long, if stood on end it would be taller than Buffalo City Hall. Ingeniously, the cylindrical grain bins and frame were joined together to create a robust mass that could resist the forces of gravity and the lateral forces of wind. Decorously, this heaving new-age monster of steel plate, girders, bolts and rivets was cloaked in a brick jacket of world-beating dimensions. It was this brick jacket which had the hole.

How would we approach the problem and what would we advise Comerford to assure the best outcome for the city? We both called Comerford in the days after the event. He did not return the calls.

Our approach would be to gather as much information as we could, beyond what our combined 75 years of experience in local architecture and preservation had instilled. First, we’d have turned to materials at hand. The first and most important document was the 1990 landmark application. It is what we automatically did while on the Preservation Board. This one was an old friend. We worked on it in 1989 and 1990, and helped steer it to Common Council approval in the face of a demolition threat from then-owner Pillsbury, which abandoned the elevator in order to eliminate the jobs of the last grain scoopers’ union in the United States. (It was the Buffalo Scoopers Strike of 1898-1899 that led to the formation of the International Longshoreman’s Association.)

This one document, had Comerford consulted it, would have been enough to calm any fears of building collapse.

The application includes a copy of an article published in Engineering News and American Railway Journal in early 1898 which included detailed descriptions of the structure, photographs of the building under construction, and diagrams of the six principal types of support columns as well as the unique steel grain bins.

For someone with training and experience, it would have been possible to extrapolate in the mind’s eye a three-dimensional model of the structure. Something akin to the Tinker-Toy or Erector sets children of yore could have built. The Great Northern would have been the Mother of All Erector Sets.

Having built the frame and attached the steel cylinders, one could easily imagine wrapping the thing in cardboard and aluminum foil for more verisimilitude. Eventually the model would end up in the basement or attic, next to science fair exhibits and other things too important to throw out. Over the decades it would have been knocked about and had the cardboard damaged or foil torn, but nothing that couldn’t be patched when discovered by a new generation.

What would the Engineering News “assembly instructions’ have taught you? First, that the bones of the structure were, if anything, over-designed. The principal support columns began at basement level with 30” x 29 “ box girders and held up giant circular girder over 38 feet in diameter. The steel bins were bolted to these, and, fastened between them the support columns rose to the bin tops to support a vast work floor composed of 6-inch I-beams resting on trusses and the bin tops. The walking surface was steel plate.

Above this, exactly like the central aisle in a basilica, the central columns rose to the top of a four-story cupola. Each pair of columns—20 pairs in all—supported a network of rafters (5-foot steel I-beams), girders, and braces. These industrial-strength framing units, or bents (imagine an Amish barn-raising), were connected by a series of girders that began with one eight-feet deep at the intersection of the roof an cupola, surmounted by one five-feet deep supporting the second floor of the cupola and so on to the roof. There, a ridge beam of perhaps 30 inches depth joined all the bents together at the apex of the building, plus one half-bent hung from the north and south ends of the cupola. All gravity and wind loads were transferred to the central columns and to the basement, and thence, by means of some 6,000 pilings, to bedrock.

The scale of the cupola and roof is suggested by the shadowy figure in a long-exposure photograph of the distribution floor taken by documentary photographer Jet Lowe.

But Jim Comerford didn’t avail himself of this information. It would have instantly disabused him of his belief that “the entire cupola could blow off,” akin to a metal garden shed placed on bare ground.

Mistakes can be fixed

Comerford assumed the north end of the cupola was teetering dangerously because he assumed the brick cladding supported it. Yet photos and video viewed by Comerford show the brick wall clearly built in front of the plane of the cupola, not designed to support it.

Comerford’s “fear of cantilever” is simply irrational when faced with the evidence, to say nothing of the documentation on hand in City Hall or a mouse-click away. As our model shows, the last bay of the cupola is hung from the ridge beam, just like similar structures are hung from the ridge beams of barns.

The Commissioner says his emergency order relied in part on submissions provided by owner ADM. Those are so compromised by cringe-worthy couching, narrow scope, lack of rigor, and a total lack of evidence—even simple photographs—that a reasonable person would not have put much stock in them. Yet Comerford parroted the hired-gun materials provided by a negligent owner liberally and met extensively with ADM lawyers to review them.

It is rationale for demolition, much less an emergency, provided by owner ADM that is thinly supported and teetering. A page-and-a half structural assessment of the Great Northern by engineer John Schenne is the chief evidence. There are no exhibits that corroborate statements made regarding the structural stability of the Great Northern (photographs, drawings, test results). The same applies to correspondence of three other engineers included in the “Submission Concerning Emergency Demolition Order Due to Safety’ compiled by ADM lawyers.

A proper historic structure report on the Great Northern would normally be expected to run to scores, if not hundreds, of pages of fact-finding, analysis, and recommendations. We have reviewed easily hundreds of demolition requests for houses that had more documentation than provided to justify demolition of the Great Northern—because the city requires it. The Schenne “report” is grossly inadequate, unsupported by fact, and uncorroborated. At the end, he ventures that his assertions and speculations of earthquake risk, failing pilings, rusted steel spelling structural doom, are just that—opinions. Comerford should have given them the respect they deserved.

We can excuse Commissioner Comerford and his inspectors for not reading our guidebook on the waterfront’s industrial heritage or going on one of our boat, bus, or walking tours over the past 35 years, or that of others in the cottage industry of industrial heritage tours that has sprung up in their wake. But what about answering the phone or returning a call? What about reviewing City Hall files? What about examining the piles of photos and data sheets online at the Library of Congress? What about having a fresh set of eyes examining photographs and video to guard against confirmation bias? What about admitting a mistake we are all going to regret?

You can help The Campaign save the Great Northern and in its mission to preserve and enhance all the places that make Buffalo special by making a donation on our website at GreaterBuffalo.blogs.com or simply scanning the qr code below.

Paul McDonnell, AIA, former architect of the Buffalo Public Schools and chair of the Buffalo Preservation Board, is President-Elect of the NY State AIA; Tim Tielman is executive director of The Campaign for Greater Buffalo, author of Buffalo’s Waterfront: A Guidebook, and principal of Spatial LLC