Buffalo Cloudwalk: Skyway recycled.

20% of the Buffalo Skyway causes 100% of the urban harm. Why not save the other 80% and make it a sustainable urban amenity?

The New York State Department of Transportation’s Skyway environmental review process is being steered to a pre-determined outcome featuring a new inland limited-access highway with three interchanges, a de facto additional two lanes of the Thruway, and a total scraping away of 3.3-miles auto-free infrastructure, whether that is necessary or desired. What started as a good idea by Governor Cuomo in 2018—how to undo the urban damage inflicted on Buffalo by an obsolete state highway —has morphed into a $600,000,000 Trojan Horse.

We need a reset while it can still happen, as the environmental review process moves from scoping to draft stage. For starters, if a decision is made to abandon the Skyway for vehicular use and to deconstruct the damaging parts (the 3,300-foot viaduct north of the Buffalo River and its massive Thruway interchange), there is no legitimacy in removal of the urbanistically useful parts of it (14,000 feet, from the north bank of the river to Buffalo Harbor State Park). Parts that were just rebuilt at a cost of almost $90,000,000 in 2010.

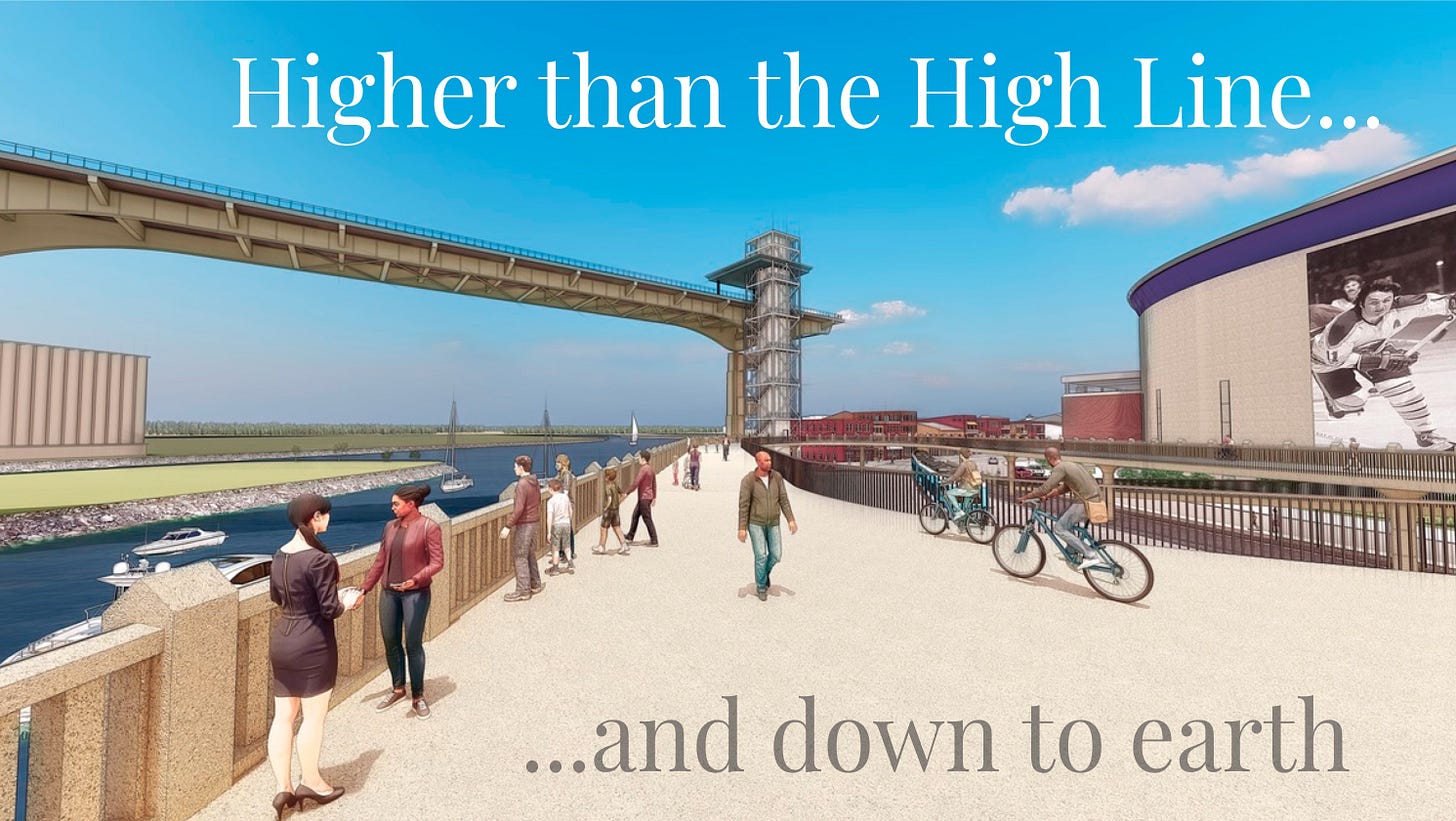

The poster child of that reset—a reset of the very idea of expressways in the hearts of our cities— must be the conversion of the former Skyway, after deconstruction of the north viaduct, to a Cloudwalk connecting the historic DL&W train shed and Central Wharf to the Outer Harbor.

This public-works project can continue to do public work by serving other transportation modes, i.e., walking, bicycling, even skiing in winter. And, oh, there is that 50-mile view across the lake. And the views of the city. And the views of the unique cultural landscape of the grain elevators along the Buffalo River and City Ship Canal. And a direct, safe route for potentially millions of users per year from downtown to the Outer Harbor.

Richard Lippes, attorney and Campaign Board member, says "This is a reasonable alternative to simply scraping away three miles of potentially transformational infrastructure built and rebuilt at great public expense. All reasonable alternatives must be considered under State and National environmental law, and we certainly will take whatever action necessary to assure that DOT and the public has this alternative to consider"

DOT owes a lot more to Buffalo than merely removing damaging pieces of infrastructure. It also must help rebuild the neighborhoods its highway policies destroyed, and their capacity for sustaining urban life. That’s something the Campaign will take up soon. Right now, Priority One is to save the infrastructure for a Cloudwalk.

The most interesting alternatives from state competition to reimagine the Skyway retained sections over the Buffalo River and south toward Buffalo Harbor State Park. The idea has been in around for as long as there have been discussions of tearing down Skyway. The Campaign for Greater Buffalo made such a proposal in 2007. The Cloudwalk is a refinement of that, which at the outset would make it possible to reconstruct the historic streets, waterways, and buildings of the Canal District.

The Cloudwalk would be active transport link (walking, pedaling, wheelchair) and observation deck. It transforms noisy, blighting piece of infrastructure into civic and mobility asset. It provides close-ups of General Mills grain elevator, which architectural historian Reyner Banham called “the most influential structure ever put up in North America,” as well as unparalleled, unhurried, and otherwise unattainable views of Buffalo’s grain elevators, a globally unique cultural landscape.

Once Cloudwalk is built to Buffalo Harbor State Park, at state DOT and federal expense, it should become part of an expanded park, along with broad stretches of never-built-upon Outer harbor lands that it overlooks.

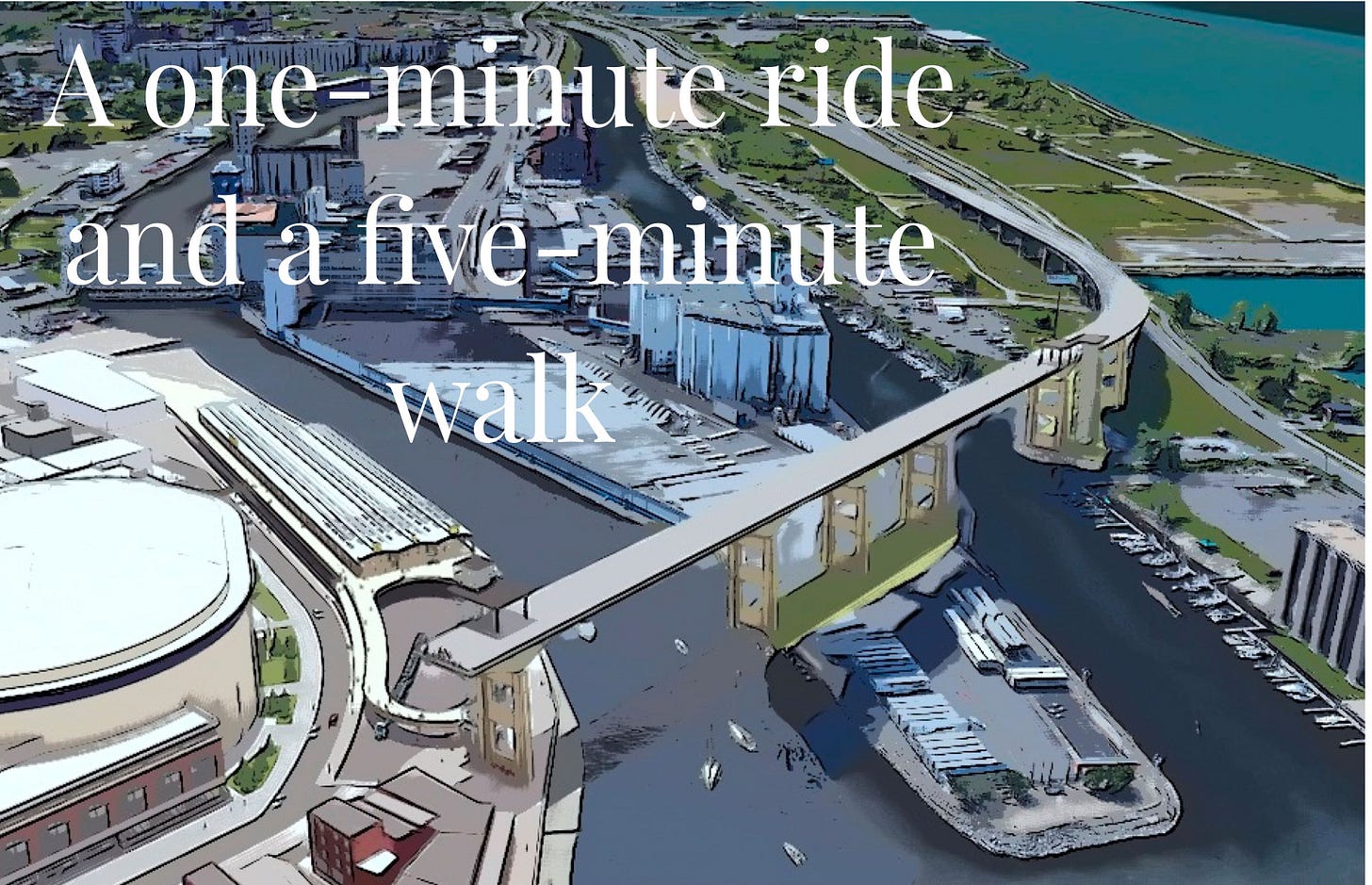

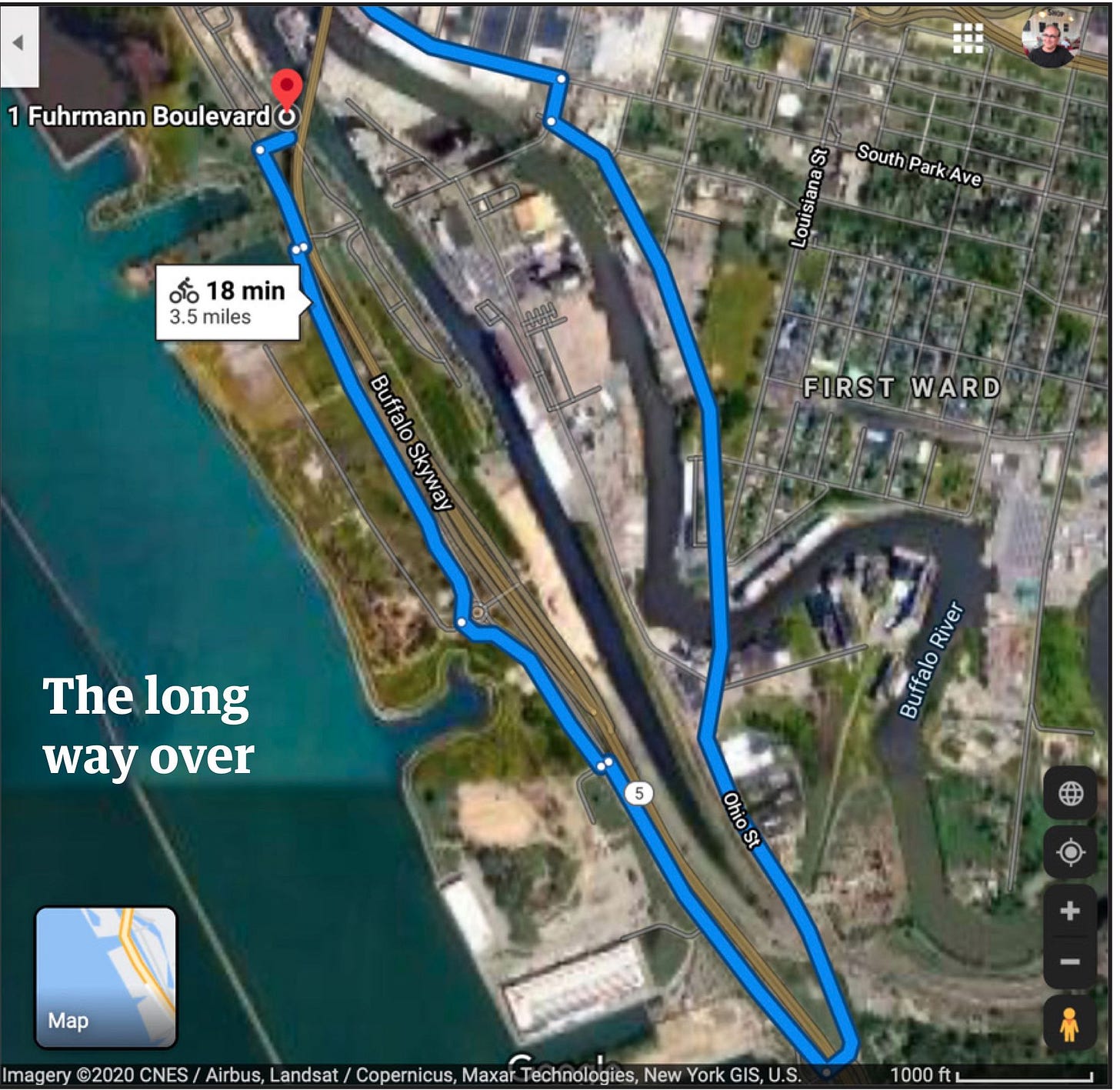

The quickest path to making the Cloudwalk viable and justifiable—besides the millions of dollars in savings over tearing it down— is to make it part of an alternative transportation infrastructure and to have it be an instrument of extraordinary time-saving trips for bike riders and walkers. The Cloudwalk would transform the lives of bike riders and walkers. For bike riders, getting to the Outer Harbor becomes a scenic one-minute ride across the Buffalo River and City Ship Canal. A walker could traverse the distance in five minutes.

What happens when you deliver such a radical improvement to a transportation mode? You induce traffic. In this case, the virtuous kind, for urban vitality as well as personal vitality.

Today, GoogleMaps informs us it takes, under ideal conditions, 18 minutes to ride from the foot of Main Street to the Connecting Terminal Elevator opposite Wilkeson Pointe park; longer to Buffalo’s iconic lighthouse (above). It only seems like forever. Walking would take over an hour and a half. That is forever, which is why no one walks.

Tossing a bone, the New York State DOT, in its “preferred alternative” for removing Skyway by building an inland highway, includes a parallel bicycle path, that stops at a highway interchange near the Tesla plant.

Fun, wow. Worthless, too, as recreation or mobility.

Were DOT were really serious about bicycles as transportation, it would suggest connecting its bike path to the Cloudwalk and the Riverline, creating a South Buffalo bicycle highway loop. A better-located South Buffalo section along Hopkins Street could act as a collector/distributor (above) the entire breadth of South Buffalo. Extensions north up Smith Street, and south to South Park, are easily imagined.

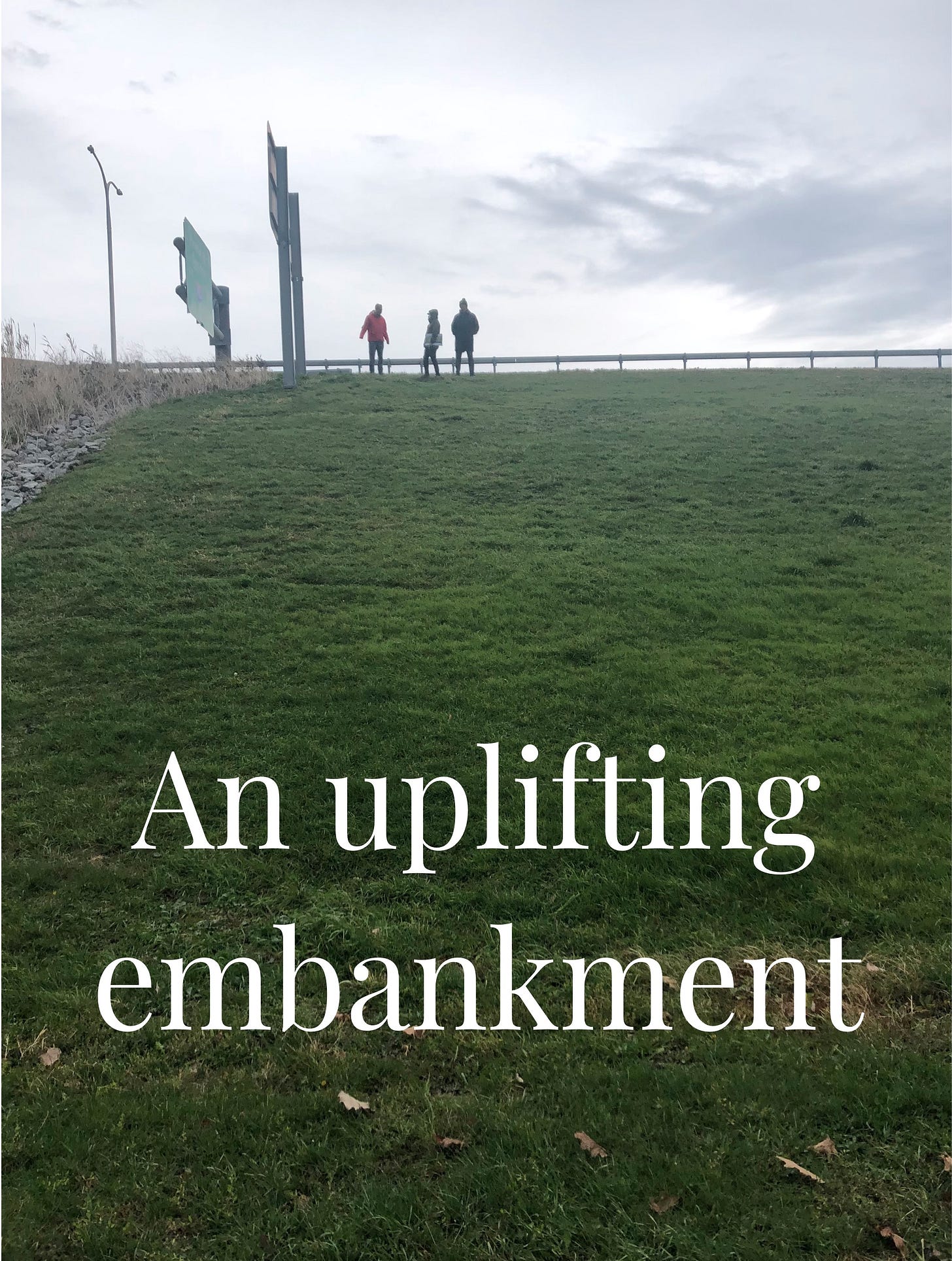

Essential to the Cloudwalk and DL&W system is the almost-mile-and-a-half embankment upon which the Skyway approach rests. Who would turn down a gift-wrapped elevated bike-and-walking superhighway that gets you to work and to relaxation without fear of car conflict or injury? It is not often one finds a highway embankment worth rallying around. The Outer Harbor embankment may be first such in the country, and would turn the symbolism of the old highway on its head.

The Embankment is a resource worth saving, gliding over five underpasses, providing otherwise unavailable views of the lake and grain elevators, and grassy slope for playing, picnicing, sledding, or viewing sunsets. No better stage and no better entertainment.

The Cloudwalk access system is loosely modeled on the system at Walkway Above The Hudson State Park in Poughkeepsie, which, even in a much smaller city, demonstrates the viability of the concept. In Buffalo, the Cloudwalk would perform a real transportation function, linking the Riverline, Shoreline, and Empire State trails, reducing the bicycling time and distance from downtown to the Outer Harbor by 90%. It is also a much safer route, with five underpasses eliminating car conflicts. It would also make the Outer Harbor accessible to pedestrians in ways a seasonal ferry operating every 30 minutes during the day does not. The Cloudwalk would be a landmark connecting landmarks in an intuitive way, which would be a great help to potentially millions of annual visitors, many of whom will be strangers to the city.

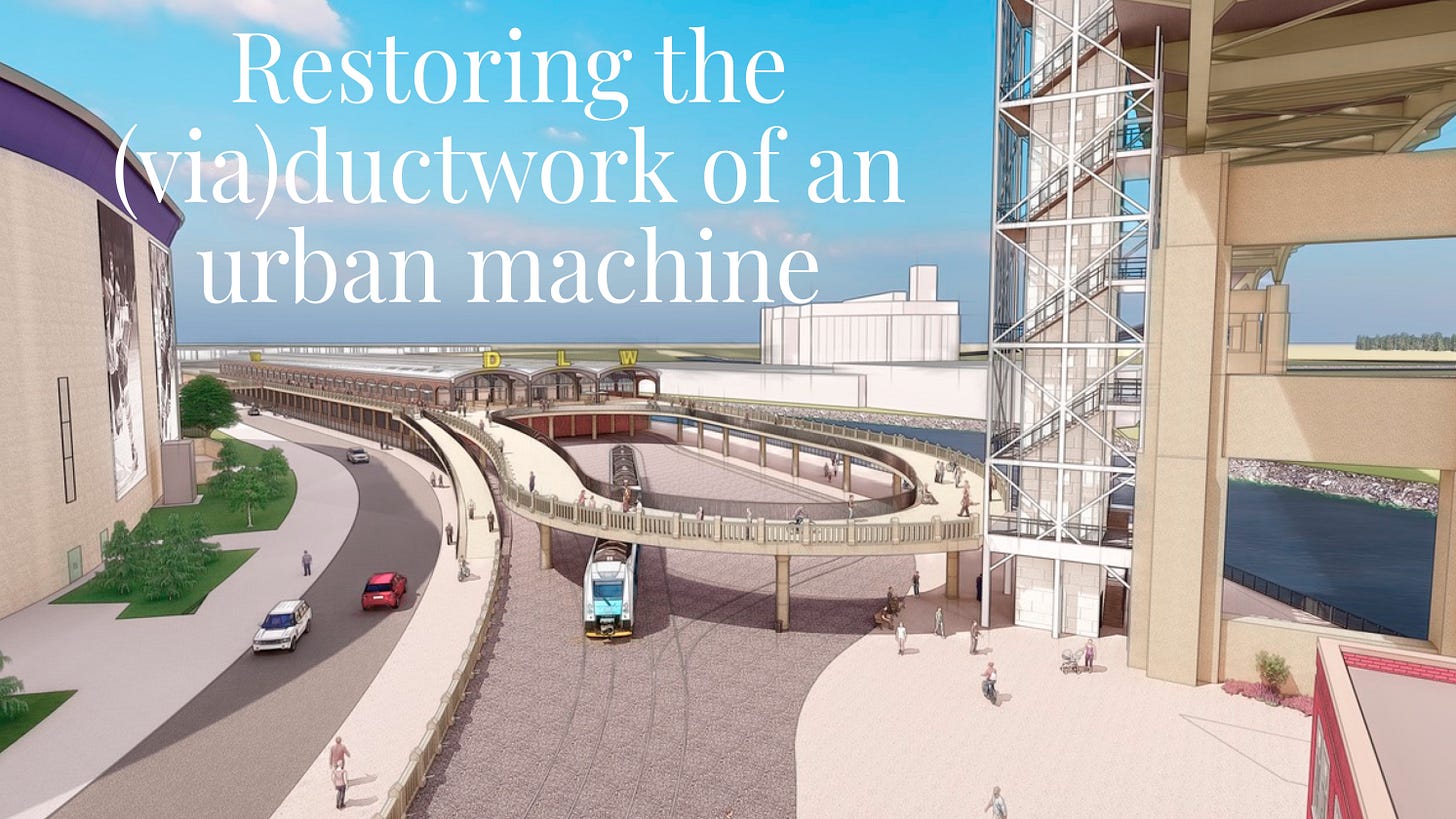

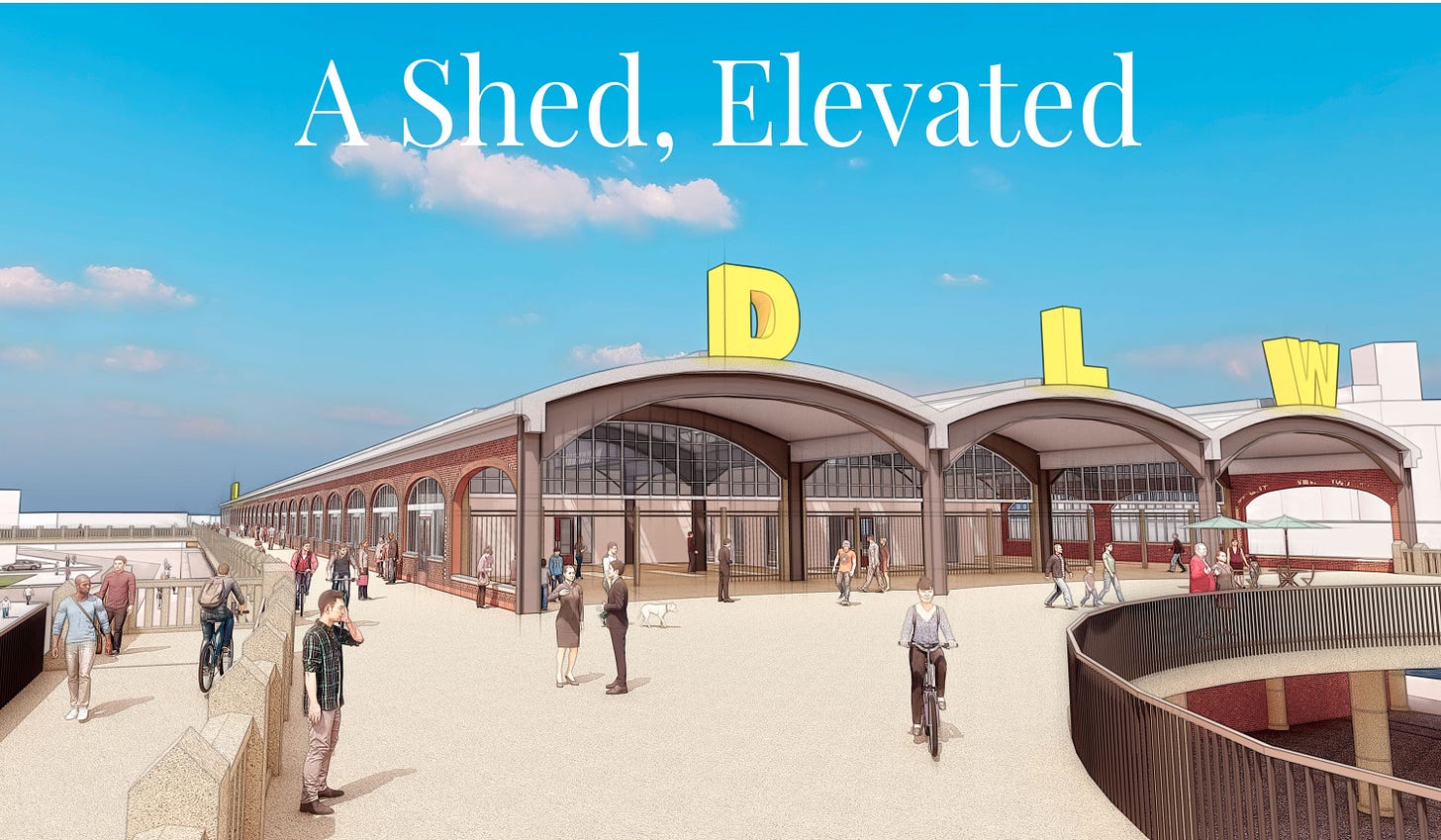

The DL&W trainshed, hundreds of feet long, is an engineering marvel. Its re-development has been a conundrum. The DL&W was built to connect A to B. That is its nature, and therein lies the solution. It cannot succeed without playing the role of connector again. To do that, its viaducts to the west and east must be re-established in a new form. It must serve pedestrians and bicyclists, both nearby in the Canal District and Erie Basin, as well those using Riverline, the cross-state Empire State Trail, where it would serve as iconic symbol, as well as those visiting newly accessible DL&W and Cloudwalk. The Campaign for Greater Buffalo has long proposed rebuilding entire deck that station once stood on, but simply building a “donut hole” viaduct, with void representing missing station, might be cheaper, easier, and better. Viaduct also acts as crossing over Metrorail tracks to Central Wharf and Canal District.

The foot of Main Street is a dead end in more ways than one. It would be transformed as part of a dynamic three-level circulation stack of pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure. It would provide ever-changing views of a working river, a working train yard, and people moving about on three levels. Visitors would be actors and audience of communal life. In aspect from above or below, the DL&W viaduct would be a swooping, looping piece of the cityscape. A glass-walled Cloudwalk elevator (rather than masonry, as shown here) would add visual interest day and night.

The view from the “front porch”of a reborn DL&W trainshed and viaduct would be a unique urban scene: the Cloudwalk, Metrorail operations, the inner harbor, the lake, and Times Beach, as well as an inviting glimpse of the Canal District beyond supermurals of Sabres greats on the Key Bank Center. Mindful design can make a useful thing a beloved thing. Sitting in a rocking chair, it would be a better place to be than, say, overlooking the parking lot at Cracker Barrel.

The DL&W viaduct is high above grade, as New York’s High Line, but would also be open for bike riders and be part of a transportation system, rather than purely recreational. The Cloudwalk elevator and stair is the epitome of useful: it elevates users 100 feet to a speedy and scenic connecting route to the Outer Harbor and points south. That’s a lot higher, and a lot more useful, than the High Line.

The DL&W trainshed is an evocative industrial shelter. It would work spectacularly well as an open-air platform for all kinds of civic, recreational, social, and commercial uses. It even has an outdoor deck of enormous proportions on the Buffalo River overlooking the Michigan Avenue bridge. A pedestrian bridge linking it to the existing parking garage and the Cobblestone Historic District at Illinois street would be an obvious enhancement.

A key to rejuvenating the DL&W is emphasize its historic character, not to waste time and treasure trying to make it into something it isn’t and should not be: a de-natured 365-day-a-year indoor shopping mall in an environment that, experience shows, is only optimally active during fair weather months. To be a success, the DL&W must have ramped access at multiple, visible points to advertise accessibility in easily understood ways.

This is as good an image as you’ll see of what DL&W train shed can be, and the unique qualities of the revolutionary Bush-style train shed (above, at a Chicago station c1911). Abraham Lincoln Bush (1860-1940) was the brilliant Chief Engineer of DL&W from 1903 to 1909 under president William Truesdale, who vowed to build “the world’s greatest railroad” between the Hudson River and Lake Erie. After leaving to set up his own engineering firm, he remained closely intertwined with the railroad, designing massive trainsheds at either end of the DL&W mainline, in Buffalo and Hoboken, as well as the world’s two largest concrete arch bridges in between.

Bush sheds were much cheaper to build and maintain, better ventilated, brighter, and less noisy than high-arched sheds built theretofore in cities, and much more weather-protected than the open canopies of small town stations. Without the abundant glazing (the sidewalls were once glazed, too) the train shed would be claustrophobic (as it possibly was during WWII, when the skylights would have been tarred over, and when the sidewalls were probably bricked in). Let the sun shine in.

Utterly unexpected is the beautiful brickwork of the walls: colorful and varied, with deeply raked, thick mortar joints. They are the walls of a Lincoln Parkway mansion. Day and night, a glowing setting for the DL&W’s famous Phoebe Snow express in the past, and of future urban adventures unnumbered.

Plans are underway to restore transportation function to part of long disused DL&W viaduct and embankment (below, c1950, Buffalo History Museum collection), in form of The Riverline between Moore and Smith streets. The Cloudwalk and DL&W infrastructure must be rebuilt to Riverline. Connecting existing parking ramp by pedestrian bridge over South Park Ave., as part of a “park once” system allowing drivers to become walkers and riders once in neighborhood is obvious.

South Park Avenue between the DL&W and the Key Bank Center is one of the most challenging environments in Buffalo to develop–it is a reason the DL&W has languished. Making it a hub of a green transportation network—bikes, trains, buses, and walkers and connecting it to the Cobblestone District, Canal District, Old First Ward, and the Outer Harbor would be transformative. Joined, the DL&W and the Cloudwalk can become mechanisms of enhanced urban activity, understanding that “attractions” aren’t urbanism—urbanism is the attraction. Biking and walking are the most ecologically sound ways to get around, and taking public transportation is second best. The Cloudwalk and DL&W would combine all three (Metrobus is there, and a new Metrorail station is planned). For good measure, it also encourages change-of-mode from cars by connecting to parking ramp and lots.

Skyway converted to Cloudwalk and “smart streets” flanked by bike paths and “super sidewalks” (as at already improved Ohio St.) into city would be better, cheaper, and faster than current preference of NY DOT for inland highway to replace demolished Skyway. In either event, some Skyway traffic would divert to local street approaches to downtown. A new street on disused rail yard on west bank of City Ship Canal, with fixed bridge at the head of navigation, could connect to Kelly Island and S. Michigan Ave. Improved local streets could handle with minimal delay Skyway drivers that do not choose to divert to much-improved Thruway (which now has full-speed cashless tolling, eliminating Lackawanna toll barrier backups and lesser slowdowns at Hamburg, Blasdell exits). Citizens of Old First Ward, The Valley, and the Elk Market-Perry neighborhoods would have two good options to the waterfront.

Save all of it and walk/bike all the way to Niagara Square. Keep the elevator for Canalside.

NFTA trains should access the remaining skyway for those who cannot walk or bicycle to the Outer Harbor from the City. This should be the only public transit to the Outer Harbor from the City, except by auto via Tifft and Fuhrmann Blvd. This plan will enhance the Outer Harbor Park, City living, and put traffic onto I 190 from NY 5 to the South. Access to the City will be mostly Elm-Oak Arterial or Church St. for personal transit workers from the southern suburbs.

David Stout, Angola, NY