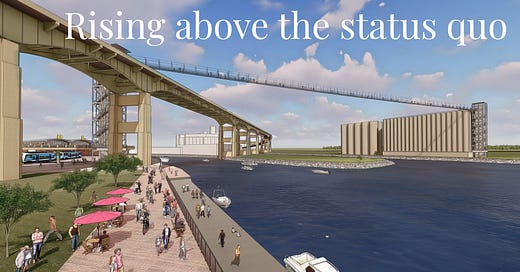

Bridging the access gap on the Buffalo Waterfront

Outer harbor plans have car dependency baked in. Millions of annual visitors and transit users are denied easy access. There is a simple solution.

Cars first, everything else after, if at all. That is the way of development in Buffalo. Bad enough when it comes to sustainability, access for those without cars (sometimes, controlled access is what it is all about), poor urban design, undermining of public transit—the full litany of things we all believe we’d resist if presented half the chance. These things compound when public projects are involved. Like waterfront development in Buffalo. From the 1970s, with Erie Basin being a road and parking lot with a 4-foot-wide sidewalk along the water, to the present, with millions of dollars being spent to develop lands out of reach of all but drivers. It is normal, the status quo.

How about we subvert the paradigm? Should you have to gaze longingly from Central Wharf 800 feet across the river to the Outer Harbor and realize it is all but impossible for you to get there, unlike the cars thundering overhead on the Skyway? Maybe you parked your car, set out for a stroll, and would like to get to the Outer Harbor without packing up and going back to the car to enjoy what should be a 5-minute walk away.

Especially when there is a 5-minute solution available: a simple, age-old bridge design adopted by European resorts and local governments that has resulted in hundreds of ever-longer, ever-higher bridges, essential links in bicycle and active transport (engineerspeak for walking) networks. (For a hard-copy version of this article: Download the December 2021 Greater Buffalo )

These are simple wire ropes slung across mountain passes with decks of metal grids or planks hung from them. In 2015, what was then the world’s longest pedestrian bridge was built in Switzerland for the equivalent of $800,000. Pennies on the dollar for what a vehicular bridge would cost. (swissrope.com)

Switzerland has 153 of the bridges. You could build a half a dozen of these, with all the fixin’s (in the Cloudwalk’s case, elevators and stairs), for less than the cost of a highway ramp. (A Youngmann Highway/I-190 ramp built 10 years ago cost $16.5 million.)

Building these bridges isn’t rocket science, either. Swissrope.com got its start building skilifts. The leading designer of long-span pedestrian bridges in the U.S., Experiential Resources, or ERI, started as a fabricator of ziplines and ropewalks. Chief designer and co-owner of ERI, Todd Domeck, told WKBW-TV that the design has many advantages for an urban area. "They're safe. They're utilitarian. It's an economical choice to transport people, and like all bridges, inherently they bring people together. To bring people together on a beautiful structure is what we want to do." Domeck says his team could build the suspension bridge in about a year. WKBW's story is here.

ERI built the first such bridge in the U.S., nearly 700 feet long, three years ago (https://www.experientialresources.com/gatlinburg-skybridge), and is building another over 800 feet long in Michigan, with several others on the boards.

Not a toy, but transportation.

The temptation will be to view bridges like this as a toy, a recreational “attraction.” That would be a mistake. Fun they would be, but WNY has many locations that sorely lack the infrastructure necessary to address the transportation needs of those without cars.

It is a denial of service that must end. The Outer Harbor is off-limits to users of public transit in Buffalo and its northern and eastern suburbs, whether by direct route or by connecting routes. There simply is no service. Even South Buffalo residents, who live closest to the lakeshore, can’t get there on the NFTA.

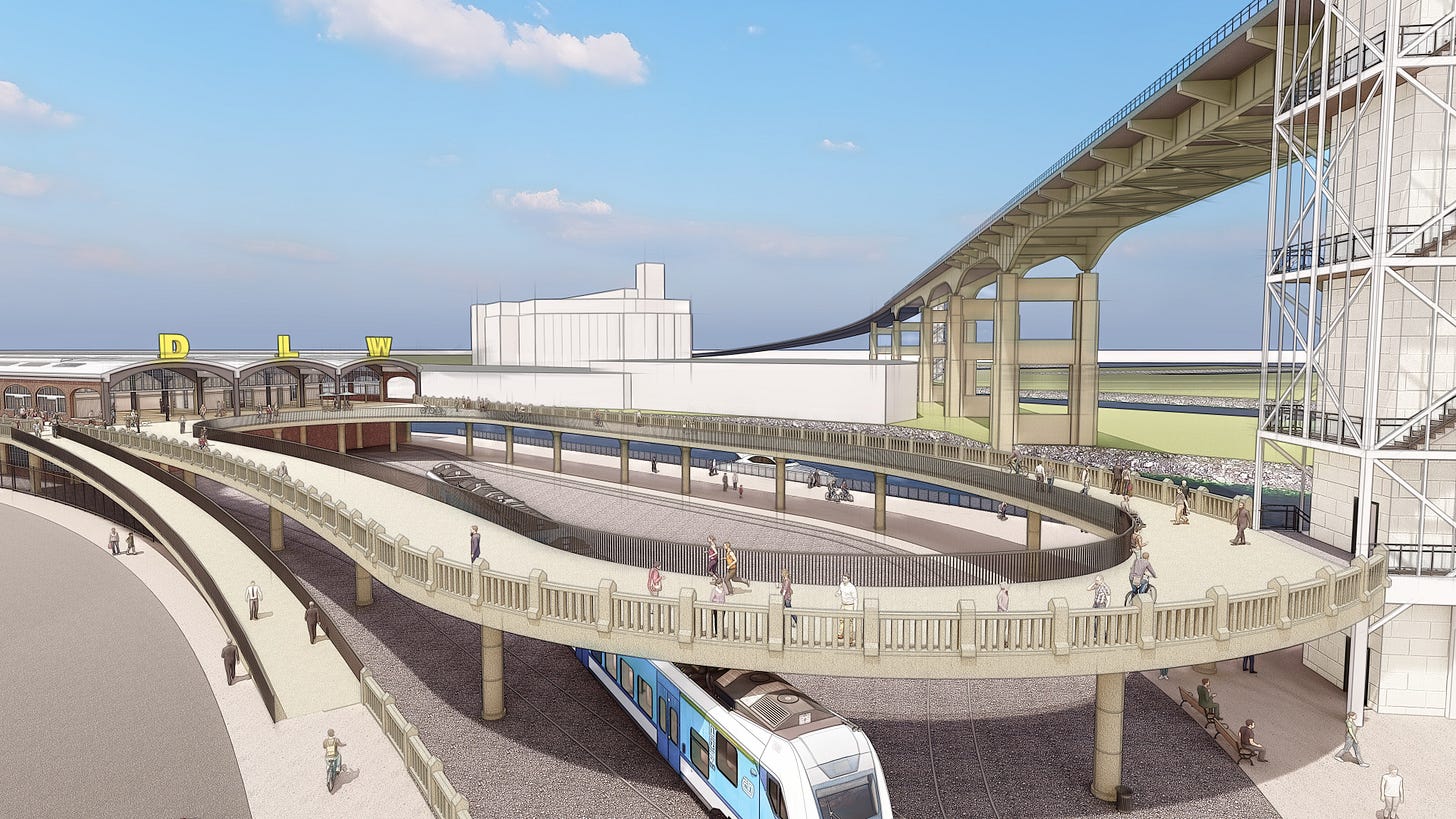

Metrorail’s new station at the DL&W can change that, if the Cloudwalk is realized and a direct connection is made to it. A simple elevator ride and a five-minute walk across the Cloudwalk would bring transit users—and other pedestrians and bike-riders—to another elevator ride to the entrance of Wilkeson Pointe Park. That is a gigantic bonus to everyone with a public transit pass—the new access is free, and a reason to use weekend service. For others, the new access is another reason to leave the car and its hassles at home. For the Canal and Cobblestone districts, that is a huge stream of foot traffic, especially during summer.

As hockey and concert fans know, taking Metrorail from the UB or LaSalle stations is a breeze for northtowns or North Buffalo residents—you avoid all the auto congestion and expensive parking near Key Bank Center. Imagine a summer weekend, being able to ride Metrorail directly to the Cloudwalk, DL&W, and Central Wharf, and then talking a five-minute walk across the Cloudwalk to a picnic at Wilkeson Pointe—or on the roof of the Connecting Terminal elevator.

The US Department of Transportation is trying to encourage transportation projects like this by awarding “Exemplary Human Environment Initiatives’ to both encourage nonmotorized transportation and to enhance “the environment for human activities.” As examples of award-worthy projects USDOT cites encouraging greater use of bicycling and walking; providing “noteworthy” facilities for bicycling and walking and integrating these into highway and transit development; incorporating historic preservation activities into project development and design; transportation and land use integration; and creating or enhancing opportunities for recreational activities. A Cloudwalk would fulfill all of those goals.

A restorative development tool

The members of the Campaign for Greater Buffalo have advocated for preserving, restoring, and appreciating the historic assets of the Buffalo River since the 1980s. This includes creating the Cobblestone Historic District and waging a federal court battle to save and restore the Commercial Slip, Central Wharf, and the Canal District’s historic streets.

Over the last two years The Campaign developed and publicized a plan for a post-highway downtown, the Big Picture. (See greaterbuffalo.blogs.com) The first part released publicly was to remove the Skyway and its interchange with the Thruway, allowing for the reconstruction of Terrace Park and hundreds of housing units, while adapting the bridge over the river for bike and pedestrian access between the foot of Main Street and the Outer Harbor. It was called the Cloudwalk.

Closing the Skyway fell by the wayside in community skirmishing over highway-removal priorities, a truly bad NYSDOT preference for a replacement highway, and the swift fall of Governor Andrew Cuomo. This dictates that the goals of historic preservation and universal access to the Outer Harbor be met by other means.Those goals are more important than ever to the success of both the Inner Harbor, Outer Harbor, and social justice. Recently, the Empire State Development Corporation's Erie Canal Harbor Development Corporation approved controversial plans for spending millions of dollars on an outdoor concert facility at the far south end of its Outer Harbor lands. The plan is to take the decades-old summer concert series from downtown, where it is accessible to everyone, and place it where it is only practically accessible by car.

Congressman Brian Higgins has unveiled proposals for expanding a public park along the south bank of the Buffalo River from the Buffalo Light upstream to the head of Fuhrmann Boulevard and a proposed boardwalk and park connecting stretching to the Connecting Terminal Elevator. Public transit, bicycle, and, pedestrian access are overlooked, other than as an adjunct to existing roadways. Those impose an almost eight-mile roundtrip barrier from Central Wharf on walkers, bike riders, and transit users.

The tremendous unspoken success of the Canal District and Central Wharf is their accessibility and use by all classes of residents and visitors. That springs directly from the fact that they are directly on Metrorail at the base of downtown. We must extend that success to the Outer Harbor. Especially in light of the vision set forth in the 2004 masterplan mandated by the federal district court, wherein the Canal District is to be built-out in the manner the neighborhood was before being demolished for, among other things, the Skyway and Memorial Auditorium. The Canal District and Outer Harbor would be two mutually supportive parts of a livable whole. The Canal District being historically dense, complex, and full of urban recreational opportunity, and the Outer Harbor offering open-space recreation and learning.

But the livable whole can only exist if everyone can benefit. Access must not be denied by distance, cost, or season, but must be convenient, comfortable, abundant, and free. A pedestrian bridge is essential. It makes the downtown and the Old First Ward livability index go up. Soaring over social, mobility, and equity barriers, it points toward a sustainable future. And actually, it is not a new type of bridge type, but one that is thousands of years old. It only is just now becoming used in new ways, primarily in the rugged, windy, and wintry mountains of central Europe.

Niagara Falls? Youngstown, Lockport, Letchworth?

Bridging the access gap on the Buffalo waterfront is just the beginning. Regionally, long-span low-cost pedestrian bridges solve a lot of access problems particular to Western New York and nearby Canada. Think of spanning the Niagara River between Prospect Park and Clifton Hill in Niagara Falls. Connecting Youngstown with Niagara-on-the-Lake. Crossing the Erie Canal below the Flight of Five in Lockport. Economically useful all. That they’d be fun is a bonus.